003 - The Predominant Paradigms in the way of a Participatory Future Thinking in Systems - Part 1

This is reposted from our newsletter “Collaboration, Sorted - Monthly notes on shifting power and embedding participation and dialogue in democracy and organisations.”

To get these directly to your inbox you can sign up here - https://www.sortedcollaboration.com/newsletter

In my last newsletter, I imagined what a participatory future could look like. The response was galvanising. It sharpened my own curiosity about what might actually help us get there. Which brings us to the harder question. What is getting in the way.

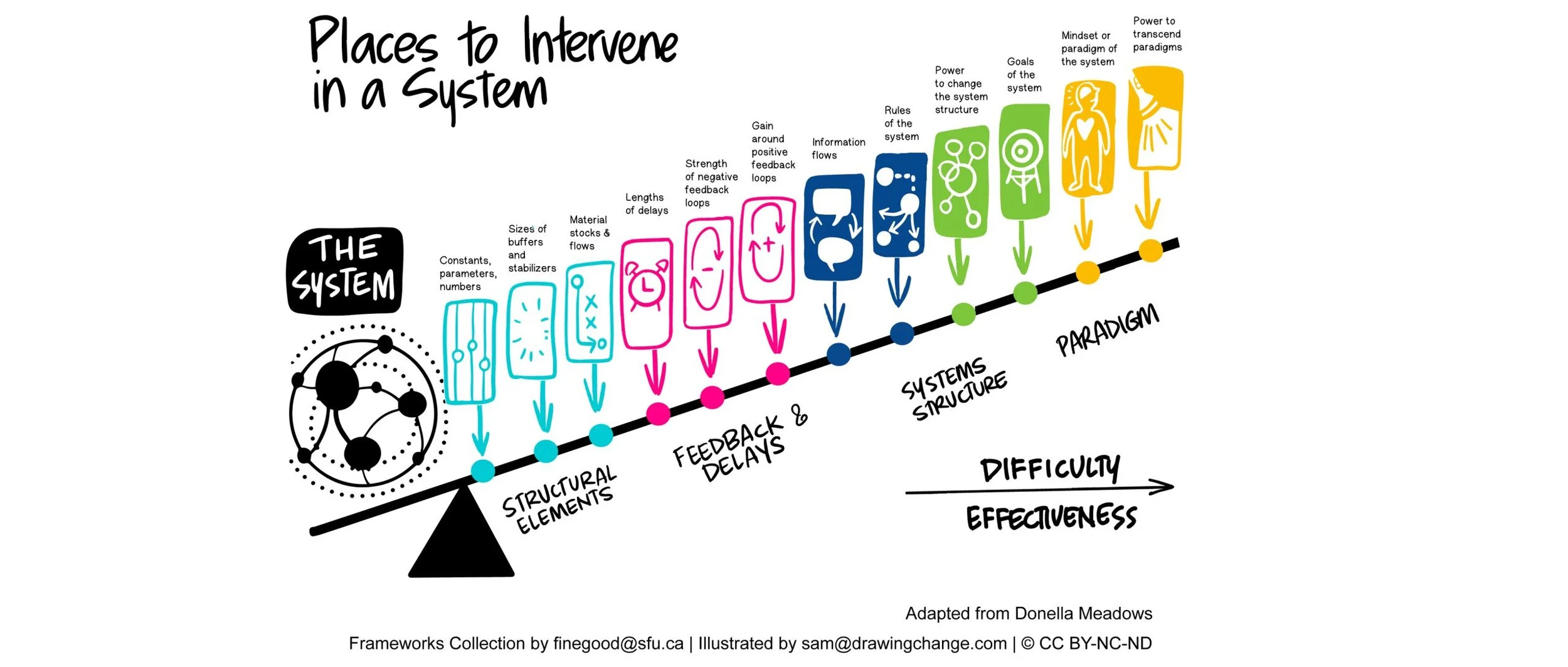

This piece marks the start of a new series. I am stepping onto Donella Meadows’ seesaw and working through it one leverage point at a time.

Her framework on the “places to intervene in a system” has shaped systems thinking for decades. It offers a simple but demanding map. Not of where change looks easiest, but of where it truly begins.

We begin at the deep end. The mindsets or paradigms of the system. The system in this case being the current political and social reality preeminent in much of the modern world.

They are deep beliefs about how the world works. The assumptions so normal we barely notice them. They decide which ideas sound sensible and which sound unrealistic. They are also the reason we cling to the familiar even when the familiar stops working.

The eagle eyed among you would have noticed the leverage point above even that. The ability to step outside the paradigm itself. The moment you realise that no worldview has a monopoly on truth. The courage to say “I might be wrong” and treat it as an invitation rather than a threat.

Which brings us back to the original act of imagination. I might be wrong that a society built on participation is the answer. You might be wrong too. But for this audience, who can probably feel the possibility in it, the exercise is worth doing.

This series starts here because everything else hangs from this point. If we want a participatory future, we have to notice the stories that keep us from building it. The myths that shape leadership, knowledge, contribution, and fairness. Myths that feel natural only because they sit so deep in the cultural soil.

Touching paradigms sounds like an experimental electronic music duo. And playing them back can be both a powerful and uncomfortable experience.

Here are four of them. The ones I see most often in political life, organisational practice, and the day-to-day business of being human. I'll explore in fleeting detail what they mean and what might happen when we start to unlearn them.

The Consumer Mindset

One of the most dominant assumptions shaping modern systems is the idea that our primary role is to consume. Services. Information. Things.

Jon Alexander in his book “Citizens”, which is a call for the named alternative, describes this as the Consumer Story. A worldview in which institutions provide and individuals choose. Agency is expressed through preference and responsibility sits elsewhere.

Once you start looking for it, the pattern is hard to miss. It goes way beyond our consumption habits. In politics, participation collapses into voting every few years. In public services, people become users rather than co-authors. In organisations, engagement means being consulted after the meaningful decisions have already been made. The system speaks and people respond.

This model is efficient. It simplifies design. It scales. But it also narrows what people are expected to do and, over time, what they believe they are capable of. When systems treat people as consumers, they train them to react rather than to shape. To optimise their own experience rather than to take responsibility for the whole.

The trouble is complex challenges do not respond well to choice alone. They require judgement, trade-offs, and collective learning. The consumer model struggles here because it is built for delivery, not deliberation.

Awareness of this preeminent paradigm starts with language. Customer. User. Audience. It continues with design. Who is invited in early. Whose knowledge counts. Where responsibility is assumed to sit. Shifting it means designing for contribution rather than feedback. Expecting people to participate not occasionally, but as a normal condition of belonging.

When people are treated as citizens rather than consumers, they do not just offer opinions. They help shape the question. They live with disagreement. They carry responsibility for outcomes they did not individually choose. The system gains depth, not efficiency. And in a world that refuses to stay simple, depth turns out to matter.

The Brilliant Man Theory

Another powerful assumption is that progress comes from exceptional individuals. The visionary founder. The heroic leader. The person who sees what everyone else has missed. It is a compelling story. Easy to tell. Easy to celebrate.

It is also misleading.

Default to this comes in every form. Shakespeare as the master of prose who shaped the English language. Marx as the architect of a worker’s revolution. Steve Jobs as the genius mind behind Apple. In each case, the figure is real and the contribution matters. But the story only works by erasing the conditions that made their work possible.

Shakespeare tuned into and put to paper a language already alive in London streets and theatres. Marx gave voice to political and economic tensions being debated across Europe. Jobs stepped into an ecosystem rich with engineers, designers, and decades of publicly funded research. None of them worked in isolation. Each became visible because they stood at the intersection of collective effort, cultural timing, and shared conditions.

Most of our institutions are still organised around this myth of individual brilliance. We reward visibility over contribution. Voice over listening. Leadership becomes something to perform, rather than a practice of creating the conditions for others to think well together.

This shapes how power is distributed. Authority concentrates around a few recognisable figures. Collective intelligence fades into the background. When progress is attributed to individuals, the systems that produced it disappear from view.

You can spot this paradigm by following the credit line. Who gets named. Who gets quoted. Whose learning is documented. And whose work remains invisible. Shifting it means designing for shared authorship and making collective insight legible. Treating collaboration not as a nice-to-have, but as cultural infrastructure.

Not being savvy to this paradigm becomes a real problem when seeking a participatory future. By refusing the logic of heroic leadership, acknowledging change does not arrive with a single face or voice. When it does show up, it is often dismissed as weak or unfocused.

The irony is that the absence of a central figure is the point. Participation spreads authorship deliberately. But in cultures trained to look for brilliance in individuals, that strength can easily be mistaken for a flaw.

When brilliance is understood as something that emerges between people rather than within them, leadership changes shape. Less spotlight. More scaffolding. And far more room for intelligence to surface from places we were not taught to look.

The Technocratic Worldview

Another deeply rooted assumption is that good decisions belong to experts. The people with the right titles and proximity to power. Expertise brings comfort. It reduces uncertainty. When the stakes are high, it feels safer to hand responsibility to those who appear to know best.

But when authority sits exclusively with experts, the lens narrows. Complex social problems are treated as technical puzzles. Human experience becomes anecdotal. Civic knowledge slips to the margins. What cannot be measured or modelled is quietly discounted.

This model rests on an unspoken belief that most people are not capable of meaningful judgement. That they lack the intelligence, discipline, or perspective to participate responsibly.

And yet this assumption rarely survives contact with well intentioned reality, let alone well-designed processes. What looks like ignorance is often the product of exclusion. When people are given time, access to evidence, and opportunities to learn from one another, their capacity expands rapidly.

Experts do matter. Just not in the way our systems usually ask them to. Their role is not to decide on behalf of everyone else. It is to contribute knowledge, clarify trade-offs, and strengthen collective sense-making. Experts have legitimacy as arbiters of evidence, not as owners of outcomes.

This distinction matters. Evidence can inform decisions. It cannot make them. Moral judgement, lived experience, and collective values do not sit within any single discipline. Governing well requires both forms of intelligence working together.

Citizens’ assemblies and co-production are examples of alternative models in practice where expertise is embedded rather than elevated. In these spaces, technical knowledge does not disappear. It becomes more accurate because it meets reality. It is tested, questioned, and grounded in lived experience.

The challenge, then, is not to reduce expertise. It is to reposition it. To move from authority to facilitation. From decision-making power to sense-making support. When expertise is woven into collective processes rather than placed above them, both knowledge and democracy get stronger.

The Myth of Meritocracy

This one is particularly resilient. It tells us that success is earned. That outcomes reflect effort and talent. That those at the top deserve to be there and those left behind simply did not try hard enough.

It is a reassuring story. It creates order. It makes inequality feel fair. Especially for those, including myself, who benefit from it of which I myself am a beneficairy

But it does not hold up well to scrutiny. Luck and circumstance shape our lives far more than we tend to admit. Where you are born. Who you know. The timing of opportunities. The structures you move through. When these factors are ignored, success is over-attributed to individuals and failure becomes a personal flaw.

This mindset quietly legitimises hierarchy. It allows power to concentrate while presenting itself as neutral. Those with advantage are over-credited. Those without are blamed. The system reproduces itself while claiming to reward merit.

You can see this paradigm at work in how leadership is selected, promoted, and justified. Credentials stand in for capability. Track records stand in for potential. The same profiles circulate through positions of influence, reinforcing the belief that talent is rare and unevenly distributed.

Approaches like sortition help puncture this illusion. By selecting people at random, they operationalise humility. They recognise that leadership potential is widespread, not scarce. That judgement does not belong to a single class or career path. And that nobody inherently deserves power over others.

When chance is acknowledged, governance shifts tone. Authority becomes provisional rather than earned forever. Participation becomes a responsibility rather than a reward. And humility replaces exceptionalism as a more realistic foundation for collective decision-making.

These mindsets do not operate in isolation. They reinforce one another. The consumer waits to be served. The genius is expected to lead. The expert is trusted to decide. Together, they produce a culture of control and deference. And they quietly define the edges of what feels possible.

Shifting this is not a quick fix. It is not a framework rollout or a policy tweak. It is a slow, reflective practice. Learning to notice the water we are swimming in. Catching ourselves when familiar assumptions slip back into place. Paying attention to what feels sensible, realistic, or inevitable, and asking who that serves.

If systems are made of stories, then systems change begins with imagination. Not the abstract kind, but the practical work of noticing. Noticing the mental models shaping your organisation, your team, your politics, or your practice. And noticing which of them no longer fit the world we are trying to build.

——

If you are experimenting with participation in your organisation, institution, or community, I would love to connect.

These small experiments matter. They are how new paradigms get tested before they become normal.

Also, would love to hear thought on what predominant paradigms may I have missed?

Where are you noticing these mindsets show up?

Until next time. Happy New Year!

Stay curious. Stay collaborative.

Ben